Tuesday, April 18, 2006

Why is Russia on Iran's side?

Russia opposes Iran nuclear sanctions as six party talks begin in Moscow on how to deal with Iran's nuclear programme.

Russia opposes Iran nuclear sanctions as six party talks begin in Moscow on how to deal with Iran's nuclear programme.Here are excerps from an excellent article on Russian-Iranian relations. You can read the full article here.

What's the importance of Iran for Russia?

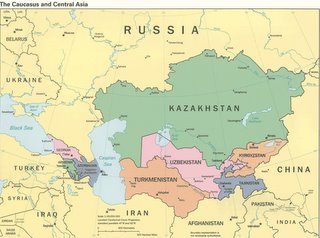

Of all the states in the Middle East, perhaps none is more important to Russia than Iran. Iran's strategic location on the Persian Gulf, its importance as a trading partner, and its ties and interests in the former Soviet republics in Central Asia and Transcaucasia have all drawn Moscow's close attention.

Russia values Iran as an important market for Russian arms and nuclear reactors, and as a way to demonstrate independence from the United States. Russia is the largest contractor when it comes to building nuclear reactors in Iran. Just recently Iran concluded a $1B deal to buy missiles and arms from Russia.

The two countries also share an interest in checking Turkey's influence in Central Asia and Transcaucasia, in opposing Taliban forces in Afghanistan, and in containing Azerbaijani irredentism and independence. In addition, Iran needs Russia's diplomatic aid in the face of U.S. isolation.

The Impact of Russia's Domestic Politics

The impact of domestic politics on Russia's policy toward the Middle East was clearly illustrated by the shift from an initially strong pro-Western tilt in 1992 to a highly nationalist thrust by the end of 1999. In part, this was a reactive change to challenges from the Russian Parliament, where three main groups of legislator vied for power.

One group supported Yeltsin's pro-Western foreign policy, which included good ties with Israel, sanctions against Iraq, and cooperative relations with the countries in the "near abroad"-the former Soviet republics where 25 million Russian still live-along with his efforts to reform and privatize the Russian economy.

A second group advocated a "Eurasian" emphasis in foreign policy, which would not focus exclusively on the United States and Western Europe, but rather on good ties with the Middle East (including both Israel and Iran), China, as well as other areas of the world. This group also promoted closer ties with the "near abroad." On domestic policy, the Eurasianists, while still in favor of reform, advocated a far slower process of privatization.

The third group comprised a combination of old-line Communists and ultra-nationalists. Though differing on economic policy, the two groups wanted a powerful, highly centralized Russia. They wanted this state to act like a major world power and adopt a confrontational approach toward

the United States, which they saw as Russia's main enemy, as well as toward Israel. In this context, they proposed renewing close ties with Moscow's former Middle East allies such as Iraq, and reinforce ties with Iran. Finally, this third group also advocated re-establishing Moscow's dominance over the "near abroad." Yeltsin's had to fight a steady movement toward a more nationalist and anti-American position in the Duma until his resignation as president on January 1, 2000.

the United States, which they saw as Russia's main enemy, as well as toward Israel. In this context, they proposed renewing close ties with Moscow's former Middle East allies such as Iraq, and reinforce ties with Iran. Finally, this third group also advocated re-establishing Moscow's dominance over the "near abroad." Yeltsin's had to fight a steady movement toward a more nationalist and anti-American position in the Duma until his resignation as president on January 1, 2000.History of Contemporary Russian-Iranian Relations

The Russian-Iranian rapprochement began in the latter part of the Gorbachev era. After alternatively supporting first Iran and then Iraq during the Iran-Iraq War, Gorbachev had clearly tilted toward Iran by July 1987. The two states solidified their ties in June 1989 when Iran's president, Hashemi Rafsanjani, visited Moscow and concluded a number of major agreements, including one on military cooperation. The military agreement permitted Iran to purchase highly sophisticated military aircraft from Moscow, including MIG-29s and SU-24s. At the time, Iran desperately needed Soviet military equipment as its air fleet had been badly eroded by the eight-year war with Iraq and it could not request spare parts, let alone new planes, from the United States.

Iran's military dependence on Moscow grew as a result of the 1990-1991 Gulf War. The United States, Iran's main enemy, become the primary military power in the Gulf, obtaining defensive agreements with several Gulf states that included pre-positioning arrangements for U.S. military equipment. Saudi Arabia, Iran's most important Islamic challenger, also acquired massive amounts of U.S. weaponry. In addition, while the war left Iraq badly damaged, its oil wealth could provide a quick military recovery if sanctions were lifted.

The war in Afghanistan, to Iran's northeast, continued despite the Soviet withdrawal, with Shi'a forces backed by Iran taking heavy losses. To the north, the USSR's collapse presented both opportunity and danger for Iran. On one hand, for example, Iran had the chance to export its influence to six new Muslim states (Azerbaijan, Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, Tajikistan, Turkmenistan, and Kazakhstan). But Iran was also challenged by some factors. In Azerbaijan, the Popular Front, which ruled in 1992-1993, urged the unification of that country with Iran's Azerbaijan area. Iran faces a similar, if far less serious problem, with Turkmenistan, whose natural gas resources might make it an irredentist attraction for Turkmens living in northeastern Iran.)

Given Iran's need for sophisticated arms, Rafsanjani was careful not to alienate either the Soviet Union or Russia during his term as president. Thus, when Azerbaijan declared its independence from the Soviet Union in November 1991, Iran--unlike Turkey--did not recognize its independence until after the USSR collapsed. Similarly, despite occasional rhetoric from Iranian officials, Rafsanjani ensured that Iran kept a relatively low Islamic profile in Azerbaijan and Central Asia, emphasizing cultural and economic ties rather than Islam as the centerpiece of relations. This was due in part to the fact that after more than 70 years of Soviet rule, Islam was weak in those places; leaders of the new states were all secular, and chances for an Iranian-style Islamic revolution were very low. Indeed, some skeptics argued that Iran was simply waiting for mosques to be built and Islam to mature before trying to bring about Islamic revolutions.

Nonetheless, the Russian leadership believed that Iran was basically acting very responsibly in Central Asia and Transcaucasia and was thus ready to continue supplying Tehran with modern weaponry-including submarines-despite strong protests from the United States. Iran's low-key reaction toward the first Muslim insurgency in Chechnya (1994-1996) and toward Russia's pro-Serb and anti-Muslim policy in Bosnia in 1993-1995 helped cement relations further.

During 1992, Yeltsin's honeymoon year with the United States--when he and Washington agreed on virtually all Middle East issues aside from Iran--the two countries clashed over Russian arms shipments to Iran. Iraq and Libya were under UN sanctions, while Syria lacked the hard currency to pay for weapons and already owed Russia some $10 billion. In contrast, Iran could supply Russia with badly needed hard currency.

In addition, despite Yeltsin's cultivation of the United States, there were a number of influential Moscow figures such as Yevgeny Primakov, then chief of one of Russia's intelligence branches, advocating a more independent Russian policy in the Middle East. Given that the United States did not have relations with Iran or Iraq, Russia could fill the diplomatic vacuum in both states. Furthermore, unlike Iraq or Libya, America's allies in the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) maintained extensive economic ties with Iran, though the Salmon Rushdie affair and the murder of Iranian exiles in Western Europe somewhat damaged political relations.

Thus, Russia had a certain amount of diplomatic cover for its dealings with Iran. Consequently, as Yeltsin came under fire from increasingly vocal members of parliament in 1993 and 1994 for being too subservient to the United States, he could point to American criticism of his policy toward Iran-which by 1993 included a promise to sell nuclear reactors-to demonstrate his independence. Indeed, one of the central issues of contention in the May 1995 Moscow summit between Clinton and Yeltsin was Russia's January 1995 decision to sell nuclear reactors that Washington claimed would speed Iran's acquisition of nuclear weapons. Yeltsin refused to back down in the face of U.S. pressures. But he did agree to cancel a proposed gas centrifuge sale to Iran--initially approved by Russia's atomic energy ministry--which might have aided Iran's nuclear proliferation, something very few Russians, including Yeltsin, wanted. Nonetheless, the Russians regularly asserted that U.S. opposition to the sale of nuclear reactors was due to commercial jealousy, not to any genuine fear of Iran acquiring nuclear weapons.

A Strategic Relationship

By the summer of 1995, Russia and Iran embarked on what the Russian ambassador there had begun to call a strategic relationship. With the first Chechen war raging and Washington now calling for NATO expansion, Russian nationalists looked to a closer relationship with Iran as a counterbalance. As an article in the newspaper Segodnia in May 1995 noted:

By the summer of 1995, Russia and Iran embarked on what the Russian ambassador there had begun to call a strategic relationship. With the first Chechen war raging and Washington now calling for NATO expansion, Russian nationalists looked to a closer relationship with Iran as a counterbalance. As an article in the newspaper Segodnia in May 1995 noted:"Cooperation with Iran is more than just a question of money and orders for the Russian atomic industry. Today a hostile Tehran could cause a great deal of unpleasantness for Russia in the North Caucasus and in Tajikistan if it were to really set its mind to supporting the Muslim insurgents with weapons, money and volunteers. On the other hand, a friendly Iran could become an important strategic ally in the future.

A Russian analyst, Pavel Felgengauer, writes

NATO's expansion eastward is making Russia look around hurriedly for at least some kind of strategic allies. In this situation, the anti- Western and anti-American regime in Iran would be a natural and very important partner. Armed with Russian weapons, including the latest types of sea mines, torpedoes and anti-ship missiles, Iran could, if necessary, completely halt the passage of tankers through the Strait of Hormuz, thereby dealing a serious blow to the haughty West in a very sensitive spot. If, in such a crisis, Russian fighter planes and anti-aircraft missile complexes were to shield Iran from retaliatory strikes by American carrier-based aircraft and cruise missiles, it would be extremely difficult to 'open' the Gulf without getting into a large-scale and very costly ground war.

Russian-Iranian economic and military relations continued to develop with reports of Russian plans to sell Iran $4 billion of military and other equipment between 1997 and 2007 if Iran met its financial obligations-a provision that may have been inserted because of low oil prices and Iran's weak economy.

Despite some areas of friction, the Russian-Iranian relationship has proved beneficial to both countries. From Russia's standpoint, Iran (despite occasional problems paying its debts) is an excellent arms client and market for nuclear reactors. It has also been an ally against what Moscow has called "U.S. hegemony" as Russian-American relations deteriorated; in helping to bring at least a limited peace in Tajikistan; in confronting the Talibans in Afghanistan; and in containing Azerbaijan. At a time when Russia has not fully recovered economically, with its armed forces (especially its navy) very weak, having Iran as an ally makes excellent diplomatic sense, since an independent Iran helps prevent the United States from fully dominating the Persian Gulf, where Moscow has important interests.

From Iran's point of view, Russia is a secure source of sophisticated arms; a diplomatic ally at a time when the United States has sought to isolate it; an ally in helping to curb Azerbaijan's possible irridentist threat; and an ally in helping stem the terrorist threat and drug flow from Afghanistan.

- Assareh

<< Home